Bridget Bishop was not the first to be accused of witchcraft but she was the first to be executed for the crime in 1692. At the time of the trials, she was married to her third husband, the elderly sawyer Edward Bishop. When arrested, Bridget was living on the property she inherited from her second husband Thomas Oliver, on present-day Washington Street in Salem Town.

On April 16, two women ‑ Bridget Bishop and Mary Warren – were newly accused by the afflicted girls. Two days later, complaints were filed against the two, as well as against Giles Corey and Abigail Hobbs. Those who claimed to be tormented were Ann Putnam Jr., Mercy Lewis, Mary Walcott, and Elizabeth Hubbard. Bishop was arrested on April 19 by Salem Marshal George Herrick and taken to Ingersoll’s Ordinary in Salem Village (modern-day Danvers) where the examinations were held. The afflicted girls writhed and convulsed. “She calls the Devil her god!” said Ann Putnam Jr. Judge Hathorne accused Bishop of afflicting the girls, which she denied. “I never saw these persons before, nor I never was in this place before,” said Bishop. “I am as innocent as the child unborn. I am innocent of a witch.” Judge Hathorne accused her of bewitching her first husband to death, which she also denied. The afflicted girls’ behavior was enough to convince the examiners. Bishop was held for trial in Salem jail, a short distance from her home.

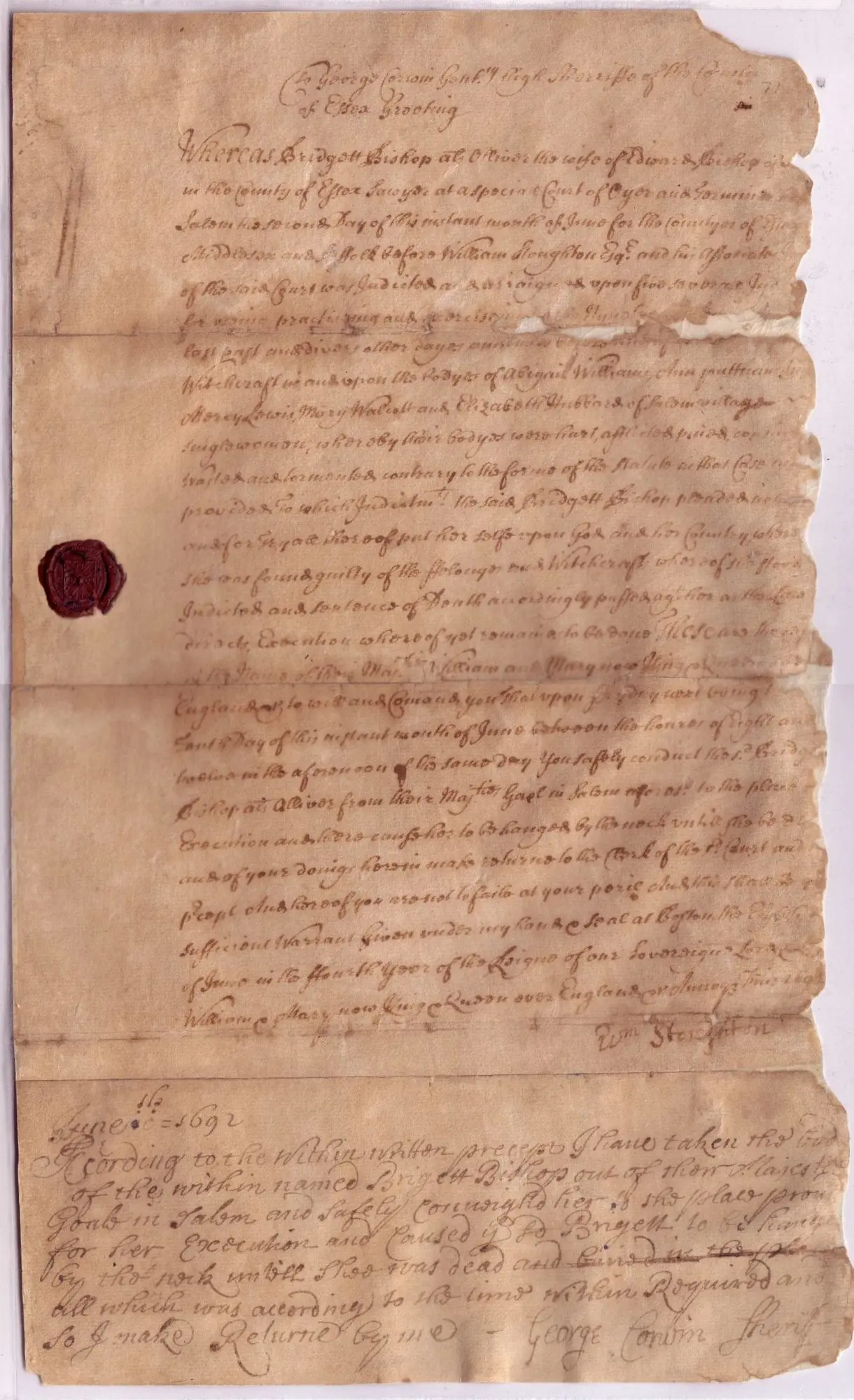

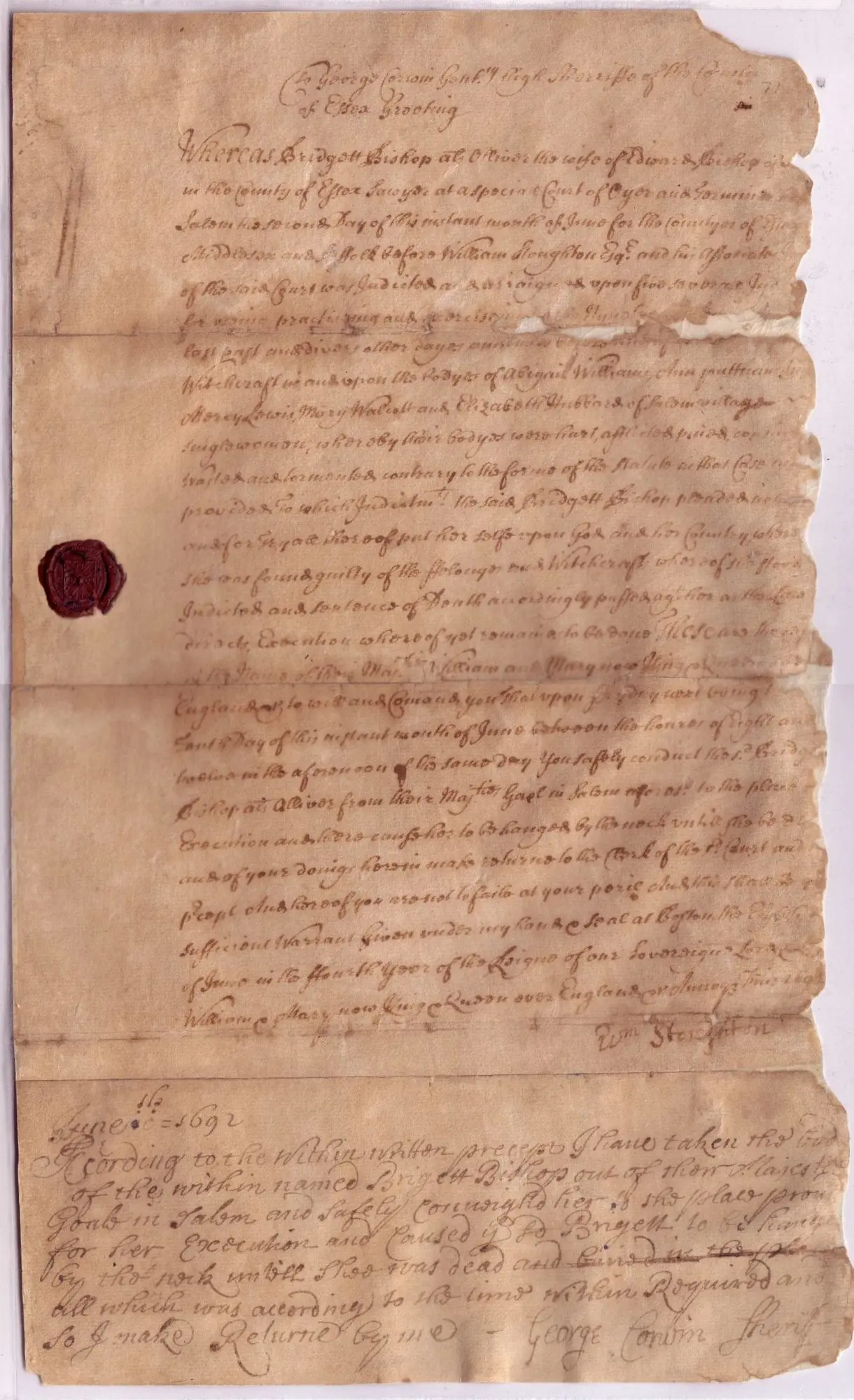

On June 2, the Court of Oyer and Terminer heard Bridget Bishop’s case in their opening session. Perhaps she was tried first because the judges felt she would be the easiest to convict, as she was a marginalized member of the community.